This One is on Me

The life-story of an old doctor who saw many changes in medicine,

in industry, in social customs, and the world in general

By Dr. James Lee Fisher

(1895-1987)

Edited by

Eric Davis & Elizabeth Fisher Davis, 1997

|

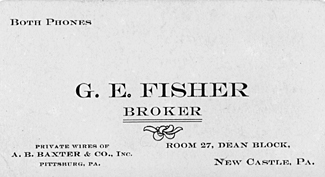

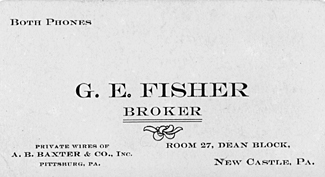

Including a collection of photographs from dry plate glass negatives taken by his father, George Elmer Fisher, a telegrapher on the Panhandle Railroad.

|

Every man should leave some record of himself. I do not remember my Grandfather Fisher and never saw Grandfather Goff, but I would like to know how they lived, what they believed in and how they met the problems of their day. They left no record.

Every man should leave some record of himself. I do not remember my Grandfather Fisher and never saw Grandfather Goff, but I would like to know how they lived, what they believed in and how they met the problems of their day. They left no record.

Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, "Every man is an omnibus in which all his ancestors ride." Being something of an ancestor now, it seems proper to put down some things about me so that my descendants will know how I lived and perhaps thus know themselves better. Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote, "Every man is an omnibus in which all his ancestors ride." Being something of an ancestor now, it seems proper to put down some things about me so that my descendants will know how I lived and perhaps thus know themselves better.

James Lee Fisher

, 1977

|

Chapter I

Carnegie, Pennsylvania

I was born August 14th, 1895 in Carnegie, Pa., the fourth child of George Elmer and Anna Martha (GOFF) Fisher. The gruesome details of my birth were often related to me by my mother. It seems that she had a contracted pelvis and bearing children was extremely difficult. The first two children were stillborn, one boy and one girl. Then came my brother George Ross Fisher [born March 15, 1887], who was born prematurely without much trouble. She was advised by old Doc Mendenhall not to have any more children but eight years later Father took her to the World's Fair in Chicago and she came back pregnant.

I was born August 14th, 1895 in Carnegie, Pa., the fourth child of George Elmer and Anna Martha (GOFF) Fisher. The gruesome details of my birth were often related to me by my mother. It seems that she had a contracted pelvis and bearing children was extremely difficult. The first two children were stillborn, one boy and one girl. Then came my brother George Ross Fisher [born March 15, 1887], who was born prematurely without much trouble. She was advised by old Doc Mendenhall not to have any more children but eight years later Father took her to the World's Fair in Chicago and she came back pregnant.

Her return

from Chicago was precipitate because of the death

of her father, James Thumwood Goff who was a prosperous farmer near

Frazeysburg, Ohio. He was driving across a ford in [Wakatomika] Creek between Dresden and Trinway in his buggy when he was accidentally drowned. It was said that he was drinking in Dresden and this made my Mother a militant prohibitionist.

Her return

from Chicago was precipitate because of the death

of her father, James Thumwood Goff who was a prosperous farmer near

Frazeysburg, Ohio. He was driving across a ford in [Wakatomika] Creek between Dresden and Trinway in his buggy when he was accidentally drowned. It was said that he was drinking in Dresden and this made my Mother a militant prohibitionist.

Mother was

born on a farm near Frazeysburg, the daughter of James Thumwood Goff [son

of Thomas Goff and Mary Ann Mart] and Nancy Ellen

[Dunn] Goff. They were prosperous farm people and their table always was

loaded with good food: fresh milk & butter from the spring house, hams

from the smoke house, chickens and eggs from the hen house. Their own honey,

fruits and baked bread were common fare. For dessert they served "float",

a cornstarch pudding with whipped cream or "ambrosia", a mixture of fruit

with shredded coconut. My mother was always a farm girl interested in birds,

flowers and gardens, but most of all in home-making. She was scornful of

father's efforts to raise vegetables and flowers. He was a town boy.

Mother was

born on a farm near Frazeysburg, the daughter of James Thumwood Goff [son

of Thomas Goff and Mary Ann Mart] and Nancy Ellen

[Dunn] Goff. They were prosperous farm people and their table always was

loaded with good food: fresh milk & butter from the spring house, hams

from the smoke house, chickens and eggs from the hen house. Their own honey,

fruits and baked bread were common fare. For dessert they served "float",

a cornstarch pudding with whipped cream or "ambrosia", a mixture of fruit

with shredded coconut. My mother was always a farm girl interested in birds,

flowers and gardens, but most of all in home-making. She was scornful of

father's efforts to raise vegetables and flowers. He was a town boy.

Grandma Nancy

[Ellen DUNN] Goff was a quiet and gentle person. At

sixty she was a wrinkled old lady in a black bonnet with ribbons under

her chin who lived in succession with her married children Lee, Thumwood,

Henrietta, Frank and Anna. Whenever there was a birth or sickness, she

was there. When she stayed too long with one, the others were jealous and

would send for her.

Grandma Nancy

[Ellen DUNN] Goff was a quiet and gentle person. At

sixty she was a wrinkled old lady in a black bonnet with ribbons under

her chin who lived in succession with her married children Lee, Thumwood,

Henrietta, Frank and Anna. Whenever there was a birth or sickness, she

was there. When she stayed too long with one, the others were jealous and

would send for her.

Grandfather

[James Wilson] Fisher [son of George Fisher

& Sybilla Margaret Shamel] was said (by my mother) to have been a fine

man. He was the station agent at Adams Mills,

Ohio on the Panhandle Railroad

which he helped to build. It is now the Fort Wayne Division of the Pennsylvania

Railroad. He died a few years after I was born and I do not remember him.

Grandmother [Margaret (Long)] Fisher and her

two daughters Ella and

Rose were cordially hated by my mother. I thought

they were alright but too mushy, always kissing me.

Grandfather

[James Wilson] Fisher [son of George Fisher

& Sybilla Margaret Shamel] was said (by my mother) to have been a fine

man. He was the station agent at Adams Mills,

Ohio on the Panhandle Railroad

which he helped to build. It is now the Fort Wayne Division of the Pennsylvania

Railroad. He died a few years after I was born and I do not remember him.

Grandmother [Margaret (Long)] Fisher and her

two daughters Ella and

Rose were cordially hated by my mother. I thought

they were alright but too mushy, always kissing me.

My birth was extremely long and difficult,

and was accomplished by forceps, which were a new invention in those days,

and only used as a last resort. I bear the scar on my forehead to this

day in a location which to any obstetrician would mean a very unskillful

application of the instruments. My eight year old brother looked at me

and thought I was a mess.

My birth was extremely long and difficult,

and was accomplished by forceps, which were a new invention in those days,

and only used as a last resort. I bear the scar on my forehead to this

day in a location which to any obstetrician would mean a very unskillful

application of the instruments. My eight year old brother looked at me

and thought I was a mess.

My

earliest recollection is about the turn of the Century. I can remember

George running into the house saying, "Look ma, I've got some more 1900

Calendars!" Another early memory was when I was four years old and father

would come home from work. He would seat me on the palm of his hand and

hoist me up as high as he could reach. It never frightened me. He was a

man who loved life.

My

earliest recollection is about the turn of the Century. I can remember

George running into the house saying, "Look ma, I've got some more 1900

Calendars!" Another early memory was when I was four years old and father

would come home from work. He would seat me on the palm of his hand and

hoist me up as high as he could reach. It never frightened me. He was a

man who loved life.

My father [George Elmer Fisher] was a

telegrapher on the Pennsylvania Railroad making thirty dollars a month for a twelve

hour day. He was a handsome man, a telegrapher in an isolated tower on

the Pennsylvania Railroad somewhere between Pittsburgh and Columbus. He

left his one-room red schoolhouse about the fifth grade, to be a water

boy for a section gang where his father was

a foreman. How he learned telegraphy I do not know, but he could read and

write and figure well enough and someone taught him telegraphy and the

Morse Code which was a new thing then (ca. 1875). At the age of nineteen

or twenty (ca. 1883-4), he was installed in a signal tower along the railroad

at Frazeysburg, a telegrapher who clacked back and forth to the train dispatcher;

received messages, set the signals, and pulled big levers which set the

switches. I was never told the details of the romance between the young

telegraph operator from Adams Mills [Ohio], and the plain farmer's daughter

of Frazeysburg. It was an incongruous match, but it lasted for 60 years,

fighting all the way.

My father [George Elmer Fisher] was a

telegrapher on the Pennsylvania Railroad making thirty dollars a month for a twelve

hour day. He was a handsome man, a telegrapher in an isolated tower on

the Pennsylvania Railroad somewhere between Pittsburgh and Columbus. He

left his one-room red schoolhouse about the fifth grade, to be a water

boy for a section gang where his father was

a foreman. How he learned telegraphy I do not know, but he could read and

write and figure well enough and someone taught him telegraphy and the

Morse Code which was a new thing then (ca. 1875). At the age of nineteen

or twenty (ca. 1883-4), he was installed in a signal tower along the railroad

at Frazeysburg, a telegrapher who clacked back and forth to the train dispatcher;

received messages, set the signals, and pulled big levers which set the

switches. I was never told the details of the romance between the young

telegraph operator from Adams Mills [Ohio], and the plain farmer's daughter

of Frazeysburg. It was an incongruous match, but it lasted for 60 years,

fighting all the way.

Father was interested

in photography and bought a camera from our family doctor [Dr. R. L. Walker

of Carnegie, PA]. It cost $60 and mother was furious because that was two

months pay. It was a big thing mounted on a tripod and he focused by covering

his head with a velvet cover while he looked at a ground glass image upside

down. After focusing he inserted the gelatin coated plates and everyone

kept still for two or three seconds while he pressed the lever. It took

clear, sharp pictures if you did everything right. He was always taking

pictures, mostly of people. He mixed his own

developer and fixer. He developed the glass negatives in a darkroom and

printed the pictures by sunlight. I still have the camera in our attic

[now in the possession of Eric & Liz Davis]. It is an antique collector's

item. I have an album of pictures taken by it which are priceless records

of our early family life [see the linked images from this page].

Father was interested

in photography and bought a camera from our family doctor [Dr. R. L. Walker

of Carnegie, PA]. It cost $60 and mother was furious because that was two

months pay. It was a big thing mounted on a tripod and he focused by covering

his head with a velvet cover while he looked at a ground glass image upside

down. After focusing he inserted the gelatin coated plates and everyone

kept still for two or three seconds while he pressed the lever. It took

clear, sharp pictures if you did everything right. He was always taking

pictures, mostly of people. He mixed his own

developer and fixer. He developed the glass negatives in a darkroom and

printed the pictures by sunlight. I still have the camera in our attic

[now in the possession of Eric & Liz Davis]. It is an antique collector's

item. I have an album of pictures taken by it which are priceless records

of our early family life [see the linked images from this page].

We lived in

a rented house in a decent part of town. It had 6 rooms and we were proud

of the inside toilet with a big box high up on the wall with a long chain

to pull. Mother cooked on a big coal stove in the kitchen and we had a

cozy fire in the dining room with a big fender

in front with brass knobs on it. We had a fire in the parlor when company

came but mostly we lived in the dining room. I can remember how father

would put slack on the fire at bedtime so it would keep. Mother would put

a big jar of buckwheat batter on the fender to raise and when I started

up the stairs I could see the firelight flickering on the brass knobs,

and the big glazed pot, and knew there would be buckwheat cakes in the

morning and the world was good.

We lived in

a rented house in a decent part of town. It had 6 rooms and we were proud

of the inside toilet with a big box high up on the wall with a long chain

to pull. Mother cooked on a big coal stove in the kitchen and we had a

cozy fire in the dining room with a big fender

in front with brass knobs on it. We had a fire in the parlor when company

came but mostly we lived in the dining room. I can remember how father

would put slack on the fire at bedtime so it would keep. Mother would put

a big jar of buckwheat batter on the fender to raise and when I started

up the stairs I could see the firelight flickering on the brass knobs,

and the big glazed pot, and knew there would be buckwheat cakes in the

morning and the world was good.

Our cellar had a dirt floor

and rough stone walls. It was reached by steps from the outside and usually

smelled of apples which we kept down there in barrels. We had no refrigeration

of any kind and it was a problem to keep milk and bread and butter. Mother

baked all her own bread and there was usually a jar of ginger cookies in

the pantry. We had a small yard in front with a picket fence and gate,

and a large yard in the back usually filled with my brother's pets.

Our cellar had a dirt floor

and rough stone walls. It was reached by steps from the outside and usually

smelled of apples which we kept down there in barrels. We had no refrigeration

of any kind and it was a problem to keep milk and bread and butter. Mother

baked all her own bread and there was usually a jar of ginger cookies in

the pantry. We had a small yard in front with a picket fence and gate,

and a large yard in the back usually filled with my brother's pets.

George

loved pets. We always had a dog and rabbits. Besides [these] there

were guinea pigs, white rats, chickens, sometimes ducks and usually pigeons.

Every time he would go out to uncle Lee's or Thum's

at Trinway he would come home with turtles or ducks which would be turned

loose in the yard. There was a high board fence around it but they were

always getting out and being searched for through the neighborhood.

George

loved pets. We always had a dog and rabbits. Besides [these] there

were guinea pigs, white rats, chickens, sometimes ducks and usually pigeons.

Every time he would go out to uncle Lee's or Thum's

at Trinway he would come home with turtles or ducks which would be turned

loose in the yard. There was a high board fence around it but they were

always getting out and being searched for through the neighborhood.

George was not very popular

with the neighbors, especially around Halloween. Those days Hallowe'en

was a succession of nights starting with corn night, then gate night, then

privy night, and ending with Halloween proper when all Hell broke loose.

On corn night the boys threw corn against the windows, on gate night many

a bonfire was fed by wooden gates, and the morning after privy night there

was much snickering among the boys and angry threats by irate householders.

To have one's privy pushed over was the height of indignity and very inconvenient,

besides. After Hallowe'en there were always indignation meetings and vows

to punish the culprits if caught, but they never were.

George was not very popular

with the neighbors, especially around Halloween. Those days Hallowe'en

was a succession of nights starting with corn night, then gate night, then

privy night, and ending with Halloween proper when all Hell broke loose.

On corn night the boys threw corn against the windows, on gate night many

a bonfire was fed by wooden gates, and the morning after privy night there

was much snickering among the boys and angry threats by irate householders.

To have one's privy pushed over was the height of indignity and very inconvenient,

besides. After Hallowe'en there were always indignation meetings and vows

to punish the culprits if caught, but they never were.

In the winter the sleighs used

to drive past our house and when we heard the bells we always ran out and

tried to hop on the runners for a free ride. The drivers would whip their

horses which added to the sport, and it was often more dangerous to get

off than it was to hop on. But falls in the snow never hurt us and we never

minded the cold. There was skating on Chartiers Creek and we all had skates

which clamped on, and were secured by a skate strap. They were always coming

off, especially if our heels were worn down. Father was an excellent skater

and thought nothing of skating up to Bridgeville and back, a distance of

ten or twelve miles. He enjoyed skating until he was in his seventies when

he fell and banged his head on the ice and didn't know where he was for

a while. Then he quit.

In the winter the sleighs used

to drive past our house and when we heard the bells we always ran out and

tried to hop on the runners for a free ride. The drivers would whip their

horses which added to the sport, and it was often more dangerous to get

off than it was to hop on. But falls in the snow never hurt us and we never

minded the cold. There was skating on Chartiers Creek and we all had skates

which clamped on, and were secured by a skate strap. They were always coming

off, especially if our heels were worn down. Father was an excellent skater

and thought nothing of skating up to Bridgeville and back, a distance of

ten or twelve miles. He enjoyed skating until he was in his seventies when

he fell and banged his head on the ice and didn't know where he was for

a while. Then he quit.

My

father was a handsome man with black hair and a black mustache. He was

active in the Methodist Church and sang in the choir. He had a way with

the ladies and mother was very jealous. She worked hard and kept borders.

At our table there were usually two borders and one or two relatives and

on Sunday a visiting minister or missionary.

They always seemed to come to our house. Father was very agreeable and

especially kind to the ladies. He played the violin,

the cornet and the banjo, all self taught, and knew a lot of funny

songs. The neighbors came over on a summer evening to hear him play the

banjo and sing [songs like] "Kentucky Babe". He taught me the songs and

I would sing with him.

My

father was a handsome man with black hair and a black mustache. He was

active in the Methodist Church and sang in the choir. He had a way with

the ladies and mother was very jealous. She worked hard and kept borders.

At our table there were usually two borders and one or two relatives and

on Sunday a visiting minister or missionary.

They always seemed to come to our house. Father was very agreeable and

especially kind to the ladies. He played the violin,

the cornet and the banjo, all self taught, and knew a lot of funny

songs. The neighbors came over on a summer evening to hear him play the

banjo and sing [songs like] "Kentucky Babe". He taught me the songs and

I would sing with him.

Anyway, we had a happy home.

We envied nobody and when the end of the month came Mother would take the

book to the grocery, Mr. Kumpf would add up the items, she would pay the

bill and he would give her a bag of candy for the kids. Mr. Porter would

come around and collect the rent, a little would be put in the bank and

we were all set. All of this out of thirty dollars a month!

Anyway, we had a happy home.

We envied nobody and when the end of the month came Mother would take the

book to the grocery, Mr. Kumpf would add up the items, she would pay the

bill and he would give her a bag of candy for the kids. Mr. Porter would

come around and collect the rent, a little would be put in the bank and

we were all set. All of this out of thirty dollars a month!

When I was eight years old

there was trouble with Father's job. He expected to be promoted to train

dispatcher and didn't get his promotion. He had joined the union, the Order

of Railroad Telegraphers, and he thought he had been found out. They usually

fired men who joined a union those days, and membership was kept a secret.

He was very unhappy and dissatisfied. About that time, he met a man who

was a broker and was looking for a telegrapher.

When I was eight years old

there was trouble with Father's job. He expected to be promoted to train

dispatcher and didn't get his promotion. He had joined the union, the Order

of Railroad Telegraphers, and he thought he had been found out. They usually

fired men who joined a union those days, and membership was kept a secret.

He was very unhappy and dissatisfied. About that time, he met a man who

was a broker and was looking for a telegrapher.

This man was not

a broker as known today. His firm had no seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

He operated what was later known as a "bucket shop".

His firm had an office in New York which leased a telegraph wire connected

with any town where they cared to open an office. The office in New York

would relay quotations on the prices of stocks to their outlying offices

where traders could buy and sell stocks on margin. The margin then was

three points which meant that a man could buy any stock for three dollars

a share. He could also sell stock he didn't have at three dollars a share.

If he thought a stock was going up, he could buy 100 shares for $300. If

he thought it would go down he could sell 100 shares for $300. If stock

cost $100 a share he could buy 100 shares, not for $10,000 but for $300

on margin. If it went against him he could put up another $300 margin or

be wiped out. If it went with him, he could take his profit and get out.

He didn't own the stock, he was betting on which way it would go. It was

gambling but at that time it was not illegal. All that Father knew was

that he was offered a job at more than he was making, but he had to move

to another town.

This man was not

a broker as known today. His firm had no seat on the New York Stock Exchange.

He operated what was later known as a "bucket shop".

His firm had an office in New York which leased a telegraph wire connected

with any town where they cared to open an office. The office in New York

would relay quotations on the prices of stocks to their outlying offices

where traders could buy and sell stocks on margin. The margin then was

three points which meant that a man could buy any stock for three dollars

a share. He could also sell stock he didn't have at three dollars a share.

If he thought a stock was going up, he could buy 100 shares for $300. If

he thought it would go down he could sell 100 shares for $300. If stock

cost $100 a share he could buy 100 shares, not for $10,000 but for $300

on margin. If it went against him he could put up another $300 margin or

be wiped out. If it went with him, he could take his profit and get out.

He didn't own the stock, he was betting on which way it would go. It was

gambling but at that time it was not illegal. All that Father knew was

that he was offered a job at more than he was making, but he had to move

to another town.

Chapter II

Freeport, Pennsylvania

Chapter II

Freeport, Pennsylvania

So

we moved to Freeport, Pennsylvania, up the Allegheny, thirty eight miles

from Pittsburgh. It was a small town and we liked it there. We lived in

a little house up on the hill on Washington

Street on the edge of town where we had apple trees and peach trees, a

well with a bucket and windlass, and the most delicious water you ever tasted.

Down the walk a sensible distance (50 feet) from the dug well was the privy,

a two-holer where flies buzzed lazily in the summer. In the winter it was

not so inviting, so chambers were kept under the beds and night time would

often find me on my knees by the bed for other purposes than prayers although

they were not neglected.

So

we moved to Freeport, Pennsylvania, up the Allegheny, thirty eight miles

from Pittsburgh. It was a small town and we liked it there. We lived in

a little house up on the hill on Washington

Street on the edge of town where we had apple trees and peach trees, a

well with a bucket and windlass, and the most delicious water you ever tasted.

Down the walk a sensible distance (50 feet) from the dug well was the privy,

a two-holer where flies buzzed lazily in the summer. In the winter it was

not so inviting, so chambers were kept under the beds and night time would

often find me on my knees by the bed for other purposes than prayers although

they were not neglected.

Strange to say, we were more

advanced there in some ways than in Carnegie with its bathroom. We had

gas lights and a gas stove in the kitchen. We bought an Edison phonograph

with a big morning glory horn and listened to Collins and Harlan sing "Bake

Dat Chicken Pie" and "The Preacher and the Bear". We bathed in a washtub

on Saturday night in front of the kitchen stove and wore long woolen underwear

and felt boots in winter.

Strange to say, we were more

advanced there in some ways than in Carnegie with its bathroom. We had

gas lights and a gas stove in the kitchen. We bought an Edison phonograph

with a big morning glory horn and listened to Collins and Harlan sing "Bake

Dat Chicken Pie" and "The Preacher and the Bear". We bathed in a washtub

on Saturday night in front of the kitchen stove and wore long woolen underwear

and felt boots in winter.

Up above us on the hill was

the McCue farm where I went every day to get the milk. They had a big swing

on a huge oak tree on the hillside and there were seldom less than three

boys on it at a time swinging out in space and yelling to make it go higher.

There was a spring there which fed two ponds where we skated in the winter

and if we fell in when the ice was thin we ran home to get warm in the

kitchen and put on some dry clothes.

Up above us on the hill was

the McCue farm where I went every day to get the milk. They had a big swing

on a huge oak tree on the hillside and there were seldom less than three

boys on it at a time swinging out in space and yelling to make it go higher.

There was a spring there which fed two ponds where we skated in the winter

and if we fell in when the ice was thin we ran home to get warm in the

kitchen and put on some dry clothes.

It was lovely

there in the summer. On my tenth birthday my brother gave me a baseball

and a new fielder's glove. Each of them cost a quarter and they were tops.

He was a telegraph operator then at nineteen years of age on the Pennsylvania

Railroad making fifty dollars a month and money was no object. The backyard

was full of pets which mother cared for most of the time because he

was working. I brought a stray black dog home

one day and Mother threw a pan of water on him to chase him away. He was

not completely discouraged by that and hung around and soon she was feeding

him scraps from the table and he was one of the family. He had a kennel

filled with straw out in the woodshed and I used to crawl in there and

talk to him. We understood each other perfectly. No one can tell me that

dogs can't talk. They just don't use our language.

It was lovely

there in the summer. On my tenth birthday my brother gave me a baseball

and a new fielder's glove. Each of them cost a quarter and they were tops.

He was a telegraph operator then at nineteen years of age on the Pennsylvania

Railroad making fifty dollars a month and money was no object. The backyard

was full of pets which mother cared for most of the time because he

was working. I brought a stray black dog home

one day and Mother threw a pan of water on him to chase him away. He was

not completely discouraged by that and hung around and soon she was feeding

him scraps from the table and he was one of the family. He had a kennel

filled with straw out in the woodshed and I used to crawl in there and

talk to him. We understood each other perfectly. No one can tell me that

dogs can't talk. They just don't use our language.

Father had a great deal of

trouble with his bile while we lived in Freeport. The spells usually came

on Sunday morning after he had been down to Pittsburgh on Saturday night.

He would have violent pains in the abdomen with vomiting. Mother would

send me down town to fetch the doctor. I would find him and go over to

the livery stable and wait while they hitched up his horse so I could ride

out to the house with him. The doctor said father's bile was too thick

and gave him medicine and he would be out to work Monday. He took me with

him several times to Pittsburgh and taught me to eat oysters on the half-shell.

Father had a great deal of

trouble with his bile while we lived in Freeport. The spells usually came

on Sunday morning after he had been down to Pittsburgh on Saturday night.

He would have violent pains in the abdomen with vomiting. Mother would

send me down town to fetch the doctor. I would find him and go over to

the livery stable and wait while they hitched up his horse so I could ride

out to the house with him. The doctor said father's bile was too thick

and gave him medicine and he would be out to work Monday. He took me with

him several times to Pittsburgh and taught me to eat oysters on the half-shell.

We had no telephone or electricity

but when I used to visit my cousin, they had a telephone and when it would

ring they used to let me listen. It was a party line and their ring was

one long and two short but when it rang everybody on the line listened

and the conversations were very interesting. It was a way of obtaining

news about births and deaths and trouble and it made greater cohesion in

the neighborhood.

We had no telephone or electricity

but when I used to visit my cousin, they had a telephone and when it would

ring they used to let me listen. It was a party line and their ring was

one long and two short but when it rang everybody on the line listened

and the conversations were very interesting. It was a way of obtaining

news about births and deaths and trouble and it made greater cohesion in

the neighborhood.

I had my first automobile ride

in Freeport in 1905. It was a red roadster with two cylinders and when

we were having a church lawn festival he brought it around and let everyone

have a ride for ten cents. It was thrilling. We persuaded my Mother to

get in the car but when he cranked up the motor she hopped out. Nobody

was going to put anything over on her, she said.

I had my first automobile ride

in Freeport in 1905. It was a red roadster with two cylinders and when

we were having a church lawn festival he brought it around and let everyone

have a ride for ten cents. It was thrilling. We persuaded my Mother to

get in the car but when he cranked up the motor she hopped out. Nobody

was going to put anything over on her, she said.

It was a great adventure to

take the train to Pittsburgh for the day. The bustle and confusion of the

traffic was exciting for a small-town boy. One had to be careful at crossings

not to be knocked down and run over by the big horses pulling drays and

beer wagons. Occasionally an automobile could be seen, but not often. It

was standard procedure to go to Boggs & Buhl in Allegheny (now the

North Side) for school clothes, then Kaufman's for lunch (always a hot

roast beef sandwich), then in the afternoon I would have an ice cream soda

at a drug store for five cents which was the highlight of the day.

It was a great adventure to

take the train to Pittsburgh for the day. The bustle and confusion of the

traffic was exciting for a small-town boy. One had to be careful at crossings

not to be knocked down and run over by the big horses pulling drays and

beer wagons. Occasionally an automobile could be seen, but not often. It

was standard procedure to go to Boggs & Buhl in Allegheny (now the

North Side) for school clothes, then Kaufman's for lunch (always a hot

roast beef sandwich), then in the afternoon I would have an ice cream soda

at a drug store for five cents which was the highlight of the day.

We lived in Freeport about

three years and then Father announced that we were leaving to go to New

Castle. I shall never forget that moving. All the crating and packing was

done by ourselves. You didn't call a mover in those days, you packed everything

yourself, then hired a man with a horse and wagon to haul the stuff to

the freight station. Father was working in New Castle and Mother did all

the packing and cried most of the time. We sold off George's pets, gave

away our big tent, threw away countless old items which would now be priceless

antiques and said goodbye to the Kelly's, the Mosses, and the McCues. My

dog went along, riding in the baggage car. I have had a horror of moving

ever since. My mother counted up in her later years that she had moved

fifty times in her married life and every time we moved my antipathy increased.

We lived in Freeport about

three years and then Father announced that we were leaving to go to New

Castle. I shall never forget that moving. All the crating and packing was

done by ourselves. You didn't call a mover in those days, you packed everything

yourself, then hired a man with a horse and wagon to haul the stuff to

the freight station. Father was working in New Castle and Mother did all

the packing and cried most of the time. We sold off George's pets, gave

away our big tent, threw away countless old items which would now be priceless

antiques and said goodbye to the Kelly's, the Mosses, and the McCues. My

dog went along, riding in the baggage car. I have had a horror of moving

ever since. My mother counted up in her later years that she had moved

fifty times in her married life and every time we moved my antipathy increased.

Chapter III

New Castle, Pennsylvania

Chapter III

New Castle, Pennsylvania

At first we lived

on Boyles Avenue and I went to Highland Avenue School. It was a good town

and father was making good money ($100.00 a month). There were steel mills

there and the Greer tin Mill was the largest in the world. Across from

the school was Boyles' field, an enormous meadow where we played baseball

and where the high school games were played.

At first we lived

on Boyles Avenue and I went to Highland Avenue School. It was a good town

and father was making good money ($100.00 a month). There were steel mills

there and the Greer tin Mill was the largest in the world. Across from

the school was Boyles' field, an enormous meadow where we played baseball

and where the high school games were played.

My brother bought me a bicycle

when I was twelve. I had a dog and there were good playmates. In the summer

we went up to Second Dam on the Neshannock Creek to swim or skated up and

down the sidewalks on roller skates. Polo was popular those days, played

on roller skates like hockey and for a quarter we could go see the professionals

play, then go out the next day and commit mayhem on each other. It was

great to get on the front seat of a summer street car and ride out to Cascade

Park which seemed the most beautiful place in the world, full of silvery

fountains and music and the smell of popcorn.

My brother bought me a bicycle

when I was twelve. I had a dog and there were good playmates. In the summer

we went up to Second Dam on the Neshannock Creek to swim or skated up and

down the sidewalks on roller skates. Polo was popular those days, played

on roller skates like hockey and for a quarter we could go see the professionals

play, then go out the next day and commit mayhem on each other. It was

great to get on the front seat of a summer street car and ride out to Cascade

Park which seemed the most beautiful place in the world, full of silvery

fountains and music and the smell of popcorn.

We lived in

New Castle about eight years with a short interlude when we moved to Newark,

Ohio for nearly a year. That was during a panic business depression about

1908 when Father was out of work and the brokerage office closed. He was

an office manager then, sometimes running the wire

himself and sometimes hiring an operator. Frequently the firm in New

York with whom he had wire connections would fold up, they were not very

stable and he would be out of business until he made new connections. The

New York Stock Exchange was clamping down on these small firms which had

no seat on the Exchange and it was getting difficult for them. This time

it was bad and he had no wire so we went to live with Aunt Ett [Marietta McCann] in Newark

and he went to work on the B & O Railroad.

We lived in

New Castle about eight years with a short interlude when we moved to Newark,

Ohio for nearly a year. That was during a panic business depression about

1908 when Father was out of work and the brokerage office closed. He was

an office manager then, sometimes running the wire

himself and sometimes hiring an operator. Frequently the firm in New

York with whom he had wire connections would fold up, they were not very

stable and he would be out of business until he made new connections. The

New York Stock Exchange was clamping down on these small firms which had

no seat on the Exchange and it was getting difficult for them. This time

it was bad and he had no wire so we went to live with Aunt Ett [Marietta McCann] in Newark

and he went to work on the B & O Railroad.

Newark, Ohio was a nice town.

We had relatives there and in Trinway and always went visiting them in

the summer. While living in Newark Mother sent me down the street to Della

Slaters to take piano lessons. I liked music but it was hard to take lessons

and practice when the other boys were out playing. Mother was a practical

psychologist and used to praise everything I played and ask me to play

them again, even the simple exercises, so she could hear them. So I would

do it, just as a favor for her then run out and play with the boys. I never

gave up the piano and later it was a great pleasure and comfort to me.

Newark, Ohio was a nice town.

We had relatives there and in Trinway and always went visiting them in

the summer. While living in Newark Mother sent me down the street to Della

Slaters to take piano lessons. I liked music but it was hard to take lessons

and practice when the other boys were out playing. Mother was a practical

psychologist and used to praise everything I played and ask me to play

them again, even the simple exercises, so she could hear them. So I would

do it, just as a favor for her then run out and play with the boys. I never

gave up the piano and later it was a great pleasure and comfort to me.

When father

got wire connections again we went back to New Castle and lived at 126

Quest Street which wound up the hillside and was so steep that we would

walk off the street at the front door and when we got back to the kitchen,

the back porch was on the third floor. New Castle's hills made for a great

sport in the winter, the coasting was thrilling. We made our skis out

of tongue and groove flooring by planing the ends thin, soaking them in

hot water and curving them upward. A leather strap was nailed across the

middle to slip our toes in and we were all set. We would come down Quest

Street at a great rate and if we could make the curve at the bottom and

come out on North Street standing up we thought it was great. I never could

jump, though. The skis always came off. There were a few automobiles those

days but not many and they were not much of a hazard. When we were coasting

or skiing they were supposed to keep out of our way.

When father

got wire connections again we went back to New Castle and lived at 126

Quest Street which wound up the hillside and was so steep that we would

walk off the street at the front door and when we got back to the kitchen,

the back porch was on the third floor. New Castle's hills made for a great

sport in the winter, the coasting was thrilling. We made our skis out

of tongue and groove flooring by planing the ends thin, soaking them in

hot water and curving them upward. A leather strap was nailed across the

middle to slip our toes in and we were all set. We would come down Quest

Street at a great rate and if we could make the curve at the bottom and

come out on North Street standing up we thought it was great. I never could

jump, though. The skis always came off. There were a few automobiles those

days but not many and they were not much of a hazard. When we were coasting

or skiing they were supposed to keep out of our way.

In 1909 I entered high school

at the old school on the corner of North and East Streets. It was old and

crowded. The upper grades went to school from 8:00 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. and

the freshman from 1:00 P.M. to 5:00 P.M. Some of the teachers taught two

grades and they had a long day. There were no junior high schools then.

In 1909 I entered high school

at the old school on the corner of North and East Streets. It was old and

crowded. The upper grades went to school from 8:00 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. and

the freshman from 1:00 P.M. to 5:00 P.M. Some of the teachers taught two

grades and they had a long day. There were no junior high schools then.

In 1911, my junior year, we

went to the new high school up on Wallace Street. It seemed very nice to

me, a big auditorium and a gymnasium. I went to school from 9:00 A.M. to

3:00 P.M. and then went downtown and cleaned Father's office for $3.50

a week, spittoons and all. In the summer I worked at the soda fountains

in Love & McGowan drug store which was the center of social life for

the younger set. People coming home from Cascade Park or the nickelodeon

would stop in there for a nut sundae or a cherry dip and it was a lively

place. I had long known that I was going to be a doctor and thought a drug

store would be a good place to work but I never got near the prescription

counter. Love and McGowan paid me $10.00 a week but I should have paid them

for all the ice cream I ate.

In 1911, my junior year, we

went to the new high school up on Wallace Street. It seemed very nice to

me, a big auditorium and a gymnasium. I went to school from 9:00 A.M. to

3:00 P.M. and then went downtown and cleaned Father's office for $3.50

a week, spittoons and all. In the summer I worked at the soda fountains

in Love & McGowan drug store which was the center of social life for

the younger set. People coming home from Cascade Park or the nickelodeon

would stop in there for a nut sundae or a cherry dip and it was a lively

place. I had long known that I was going to be a doctor and thought a drug

store would be a good place to work but I never got near the prescription

counter. Love and McGowan paid me $10.00 a week but I should have paid them

for all the ice cream I ate.

My first date with a girl was

at the end of my Junior year when it was the custom to give a dinner-dance

for the Seniors. I don't remember much about it as I was slightly delirious.

Neither Gladys Anderson nor I danced but we watched the others and had

a long talk and made great plans for next year.

My first date with a girl was

at the end of my Junior year when it was the custom to give a dinner-dance

for the Seniors. I don't remember much about it as I was slightly delirious.

Neither Gladys Anderson nor I danced but we watched the others and had

a long talk and made great plans for next year.

In my Senior

year I was seventeen years old and beginning to

realize that time was running out. The girls were looking very attractive

to me but not vice versa. I was the youngest and smallest boy in class,

a pale youth with pimples and having frequent bouts of tonsillitis. I belonged

to the Boy Scouts, went to Sunday school regularly, and my dear cousin Goldye

[McCann] had taught me to dance the waltz and two step the past summer,

but Gladys had got herself a big lanky fellow and had no more time for

me, and when the boys and girls paired off together during lunch period,

nobody paired off with me except Harold Baer and Bill Stewart, and there

was no romance in them. Something had to be done.

In my Senior

year I was seventeen years old and beginning to

realize that time was running out. The girls were looking very attractive

to me but not vice versa. I was the youngest and smallest boy in class,

a pale youth with pimples and having frequent bouts of tonsillitis. I belonged

to the Boy Scouts, went to Sunday school regularly, and my dear cousin Goldye

[McCann] had taught me to dance the waltz and two step the past summer,

but Gladys had got herself a big lanky fellow and had no more time for

me, and when the boys and girls paired off together during lunch period,

nobody paired off with me except Harold Baer and Bill Stewart, and there

was no romance in them. Something had to be done.

When the call came for football,

I reported to the squad. Nobody took me very seriously. I found an old

torn pair of football pants in the locker room. I had my own jersey and

Mother sewed up the pants and I went for practice. We practiced kicking

and running and falling on the ball. The Coach put me at playing end on

the second team and there I stayed. That satisfied me. My ambition was

to play in the annual game between Juniors and Seniors which was as important

to me as the game with Sharon or Butler. I worked hard at football practice

but the best thing that could be said for me was that I was always there.

The job of the second team was to take a pounding from the first team,

and we sure took it. After practice I would run down and clean my father's

office, go home and eat supper and then do my homework. We had study periods

in school and I was smart enough to do most of my homework then. Marian

Hover was a big help, too. She would do my Virgil translation while I would

do her German. I would go down to the Methodist Church and take her home

after choir practice on Friday nights. I took her to the Junior-Senior

banquet that year and waltzed with her. When I was leaving for college,

I asked her to kiss me good bye and she wouldn't do it. That's the way

it was.

When the call came for football,

I reported to the squad. Nobody took me very seriously. I found an old

torn pair of football pants in the locker room. I had my own jersey and

Mother sewed up the pants and I went for practice. We practiced kicking

and running and falling on the ball. The Coach put me at playing end on

the second team and there I stayed. That satisfied me. My ambition was

to play in the annual game between Juniors and Seniors which was as important

to me as the game with Sharon or Butler. I worked hard at football practice

but the best thing that could be said for me was that I was always there.

The job of the second team was to take a pounding from the first team,

and we sure took it. After practice I would run down and clean my father's

office, go home and eat supper and then do my homework. We had study periods

in school and I was smart enough to do most of my homework then. Marian

Hover was a big help, too. She would do my Virgil translation while I would

do her German. I would go down to the Methodist Church and take her home

after choir practice on Friday nights. I took her to the Junior-Senior

banquet that year and waltzed with her. When I was leaving for college,

I asked her to kiss me good bye and she wouldn't do it. That's the way

it was.

When the Junior-Senior football

game came up, I was ineligible because I was on the regular team and could

not play in class games. I got in the big one that year with Sharon. We

were way ahead when the coach sent me in and our team was penalized five

yards on the first play because I was offside. I felt disgraced but nobody

said anything. I was very surprised when I got my "N" to put on my jersey.

When the Junior-Senior football

game came up, I was ineligible because I was on the regular team and could

not play in class games. I got in the big one that year with Sharon. We

were way ahead when the coach sent me in and our team was penalized five

yards on the first play because I was offside. I felt disgraced but nobody

said anything. I was very surprised when I got my "N" to put on my jersey.

The year was not a total loss.

I was an honor student, ninth in the top ten of the class. It was the custom

at graduation for each of the honor students to give an oration. My subject

was "Modern Advances In Medicine". My material was collected from popular

magazines and Sunday supplements and was pretty lurid. The High School

auditorium was filled with fond parents and relatives of the class. Nobody

could see my knees shaking because of my long black gown when I exhorted

them to cooperate with these wonderful men of science who were doing so

much for suffering humanity. When it was over, Dr. Womer of the Health

Department congratulated me and offered his help in furthering my medical

career. It was not necessary as I was already accepted at Jefferson Medical

College [Philadelphia], but he was my friend for many years afterward.

The year was not a total loss.

I was an honor student, ninth in the top ten of the class. It was the custom

at graduation for each of the honor students to give an oration. My subject

was "Modern Advances In Medicine". My material was collected from popular

magazines and Sunday supplements and was pretty lurid. The High School

auditorium was filled with fond parents and relatives of the class. Nobody

could see my knees shaking because of my long black gown when I exhorted

them to cooperate with these wonderful men of science who were doing so

much for suffering humanity. When it was over, Dr. Womer of the Health

Department congratulated me and offered his help in furthering my medical

career. It was not necessary as I was already accepted at Jefferson Medical

College [Philadelphia], but he was my friend for many years afterward.

Please send comments and questions to:

Eric & Elizabeth Davis

Return to Top of page

©

Eric Davis 1997

Every man should leave some record of himself. I do not remember my Grandfather Fisher and never saw Grandfather Goff, but I would like to know how they lived, what they believed in and how they met the problems of their day. They left no record.

Every man should leave some record of himself. I do not remember my Grandfather Fisher and never saw Grandfather Goff, but I would like to know how they lived, what they believed in and how they met the problems of their day. They left no record.