Text-only version

Wounded escaping from the burning woods of the Wilderness

by A.R. Waud

[Library of Congress]

The Wilderness

What a Private Saw and Felt in that Horrible Place.

By Francis Cordrey, Company E, 126th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Published in the National Tribune, June 21, 1894

EDITOR NATIONAL TRIBUNE: On that beautiful moring of May 6, 1864, the sun rose on 5,000 brave comrades for the last time. What soldier will ever forget the words "Fall in! Fix bayonetes! Forward - Double-quick - March!"

On the morning of the 5th, our Colonel, B. F. Smith was relieved from the command of the brigade by Brig. Gen. [Truman] Seymour taking charge of it.

It was Colonel Smith's voice which gave the above commands to our regiment, and we felt glad in knowing our brave Colonel was with us. All through the night we had heard the enemy's axes cutting timber for protection.

Our lines moved forward, struggling through the natural abatis, while a blast of leaden hail from the enemy's thundering guns poured in the face of our advancing line : but nearer and nearer the Stars and Stripes were carried to that parapet of death.

The enemy was found to be not only strong in number, but situated in a strong position, having in front of it a large log heap as long as its line. For two long hours these logs received our lead, while the bodies of our country's defenders received that of the enemy. For a season hell laughed while Zion wept.

Here the brave bearer of our battleflag, D. W. Weleb fell dead by my side. I grabbed for the colors, but one of the other guards was the first to get them, and again they waved in the face of the enemy. Though the assult had been most gallantly made, it was repulsed with dreadful loss, and our dead and dying left bleeding in tangled brush, when our lines fell back a short distance and threw up works.

Up to this time our regiment had been on the extreme right of Grant's lines, but while entrenching, Shaler's Brigade of the First Division was thrown on our right. There had been a lull in the storm, except brisk picket firing, during which [Confederate General] Gordon, under the cover of thick woods, had thrown his troops on our right and in rear of Shaler's Brigade doubling his Brigade up on us.

Shaler and Seymour were unequal to the emergency. Had they been equal to it, they would have changed front so as to meet the enemy and would have prevented thereby the terrible destruction of life caused by an enflading fire by the enemy.

There were no cowardly soldiers then in our regiment. All such had found a hospital, or had slunk to the rear. Hence there were none to break and run; every men kept his face and gun toward the enemy, as if determined to conquer or die on the ground.

But valor could not long exist in that seething channel exposed to such a raking shower of lead. Shaler's Brigade melted away, but our Brigade remained to face the rebel storm. As before stated, it had none to break and run, and none willing to surrender, which brought on a hand to hand fight.

The sun had vailed his face beneath the horizon, as if refusing to longer witness the bloody scene. Darkness had gathered around us, and the rebels in our midst; flames issued from guns like many flashes of lightening, and the roar of musketry was like that of thunder. Shrieks and groans of the wounded and dying at our feet told that the destruction of the line was appalling. Blue and gray lay side by side, and their blood flowed into the same pool, while blue and gray stood over them with ball and bayonet, adding more crimson to the pools, and often mistaking friend for foe in the dark.

Our regiment consisting of about four hundred men on the field that day, lost 230 killed and wounded, among which was Capt. McCready, of Co. H, one of our best soldiers in camp and on the battle field. Though good, he shed no better blood than the private soldier.

Gordon gathered up his shattered remnants, taking Seymour a prisoner, and went back to his den in the woods, regretting that he had crossed arms with our gallant Brigade.

Next morning presented to us both a sad and glorious sight. It was sad to see so many of our commrades cold in death, but grand to see the stars and stripes standing, with here and there a lone soldier to mark the ground we fought to hold.

In the after part of the day, when our line fell back, a soldier lay between us and the enemy with both of his legs broken, and he cried so piteously for help that I determined to try to rescue him. He was as near to the enemy in point of distance as to us. I believe that his cries found a sympathetic response even in the bosoms of the rebels and that they would not shoot down a man who in mercy responed to the helpless man's appeal. So I made a dash for him, exposing myself to hundreds of rebel guns, and carried him back of our line, where he seemed to be satisfied, and gave me a thankful look and where I have no doubt he lay until death ended his sufferings. I was right in my opinion of the rebels; they did not shoot at me.

On the morning of the 7th both armies lay panting like two dogs after a hard fight. It was American blood against American blood and the valor was the same on both sides, but each army paused as if awe-stricken by the blood of 30,000 dead and wounded dripping from the alter of our country.

Our corps commanders were in their saddles awaiting the order to recross the Rapidan, as on former occasions. Finally the order came from headquarters something like this:

Published in the National Tribune, June 21, 1894

EDITOR NATIONAL TRIBUNE: On that beautiful moring of May 6, 1864, the sun rose on 5,000 brave comrades for the last time. What soldier will ever forget the words "Fall in! Fix bayonetes! Forward - Double-quick - March!"

On the morning of the 5th, our Colonel, B. F. Smith was relieved from the command of the brigade by Brig. Gen. [Truman] Seymour taking charge of it.

It was Colonel Smith's voice which gave the above commands to our regiment, and we felt glad in knowing our brave Colonel was with us. All through the night we had heard the enemy's axes cutting timber for protection.

Our lines moved forward, struggling through the natural abatis, while a blast of leaden hail from the enemy's thundering guns poured in the face of our advancing line : but nearer and nearer the Stars and Stripes were carried to that parapet of death.

The enemy was found to be not only strong in number, but situated in a strong position, having in front of it a large log heap as long as its line. For two long hours these logs received our lead, while the bodies of our country's defenders received that of the enemy. For a season hell laughed while Zion wept.

Here the brave bearer of our battleflag, D. W. Weleb fell dead by my side. I grabbed for the colors, but one of the other guards was the first to get them, and again they waved in the face of the enemy. Though the assult had been most gallantly made, it was repulsed with dreadful loss, and our dead and dying left bleeding in tangled brush, when our lines fell back a short distance and threw up works.

Up to this time our regiment had been on the extreme right of Grant's lines, but while entrenching, Shaler's Brigade of the First Division was thrown on our right. There had been a lull in the storm, except brisk picket firing, during which [Confederate General] Gordon, under the cover of thick woods, had thrown his troops on our right and in rear of Shaler's Brigade doubling his Brigade up on us.

Shaler and Seymour were unequal to the emergency. Had they been equal to it, they would have changed front so as to meet the enemy and would have prevented thereby the terrible destruction of life caused by an enflading fire by the enemy.

There were no cowardly soldiers then in our regiment. All such had found a hospital, or had slunk to the rear. Hence there were none to break and run; every men kept his face and gun toward the enemy, as if determined to conquer or die on the ground.

But valor could not long exist in that seething channel exposed to such a raking shower of lead. Shaler's Brigade melted away, but our Brigade remained to face the rebel storm. As before stated, it had none to break and run, and none willing to surrender, which brought on a hand to hand fight.

The sun had vailed his face beneath the horizon, as if refusing to longer witness the bloody scene. Darkness had gathered around us, and the rebels in our midst; flames issued from guns like many flashes of lightening, and the roar of musketry was like that of thunder. Shrieks and groans of the wounded and dying at our feet told that the destruction of the line was appalling. Blue and gray lay side by side, and their blood flowed into the same pool, while blue and gray stood over them with ball and bayonet, adding more crimson to the pools, and often mistaking friend for foe in the dark.

Our regiment consisting of about four hundred men on the field that day, lost 230 killed and wounded, among which was Capt. McCready, of Co. H, one of our best soldiers in camp and on the battle field. Though good, he shed no better blood than the private soldier.

Gordon gathered up his shattered remnants, taking Seymour a prisoner, and went back to his den in the woods, regretting that he had crossed arms with our gallant Brigade.

Next morning presented to us both a sad and glorious sight. It was sad to see so many of our commrades cold in death, but grand to see the stars and stripes standing, with here and there a lone soldier to mark the ground we fought to hold.

In the after part of the day, when our line fell back, a soldier lay between us and the enemy with both of his legs broken, and he cried so piteously for help that I determined to try to rescue him. He was as near to the enemy in point of distance as to us. I believe that his cries found a sympathetic response even in the bosoms of the rebels and that they would not shoot down a man who in mercy responed to the helpless man's appeal. So I made a dash for him, exposing myself to hundreds of rebel guns, and carried him back of our line, where he seemed to be satisfied, and gave me a thankful look and where I have no doubt he lay until death ended his sufferings. I was right in my opinion of the rebels; they did not shoot at me.

On the morning of the 7th both armies lay panting like two dogs after a hard fight. It was American blood against American blood and the valor was the same on both sides, but each army paused as if awe-stricken by the blood of 30,000 dead and wounded dripping from the alter of our country.

Our corps commanders were in their saddles awaiting the order to recross the Rapidan, as on former occasions. Finally the order came from headquarters something like this:

"Let the Second and Fifth Corps attack the enemy in their front, and the Sixth Corps pass to the left and engage the enemy on its right flank between it and Richmond."

"Great Scott, what does it mean?" was asked time and again until someone whispered, "The General is from the farm and shop." The expanation was so satisfactory that each soldier knew he had to "fight it out on the line if it took all summer."

So our brigade, with its corps, moved to the left toward Spotsylvania Court House. But the men were tired, hungry and sleepy, having had no rest night or day since crossing the Rapidan. On this tedious march men walked and slept at the same time; and that the reader may realize the condition that the men were in I will relate a circumstance which occured on this night march.

The infantry had been ordered to clear the road for the purpose of moving artillery to the front. The men had no sooner stepped aside than they sank down to their sleep in the mud as if it were a straw tick.

Soon the order was heard to fall in. Then the boys in their dream of fighting commenced to pound each other with guns. Of course the business soon brought them to their senses.

All night through the mud, and the next day via Chancellorsville and Todd's Tavern we marched, and at 6 P.M. on the 8th arrived in position at Alsop's Farm, three miles northwest of Spotsylvania, for the purpose of charging on the enemy's works; but the order being countermanded, we threw our blankets down and our bodies on them. We did not then fall asleep, because we had been asleep, but no sooner were we down than that the unwelcome command "Fall in" rang through our ears. I repeated the order to the boys, but was powerless to pack up my things. Communication between my brain and muscle had been cut off until the column moved. I then could grab my outfit and drag it along.

We were moved some distance to the rear to support a heavy battery, in case our help should be needed. In the light of the blazing guns and near by them we again fell down to sleep, and I think it was the soundest sleep I ever had.

In the moring when I awoke, branches of trees, and trees had been cut down during the night by the enemy's shells and shot , cannon had been overturned, and soldiers lay sleeping only to awaken to the bugle-call of heaven.

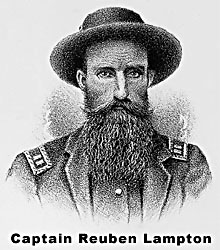

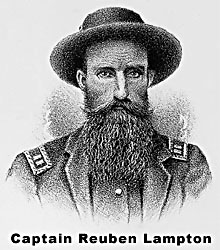

It was here that Capt. Lampton, of Co. K, added his mite to the precious price paid for the maintenance of the Union. No soldier shed better blood than that man did. He had not the silly pomposity too often found in officers, but he had something better-a true heart in his bosom, a heart that went out after the interest of men, and a soul that did not flinch in time of battle.

On the 11th we moved a short distance to the left under heavy fire, and took a new position. The roar of muskets and thunder of artillery shook the earth with their fearful detonations.

Since the morning of the 5th our regiment had held a position in the front line-of-battle of its brigade, a fact for which I cannot account; unless it was believed by the War Department that the 126th Ohio could put the rebellion down if backed by enough men, or there may have been some pecularity about the regiment that the General desired to have it killed first that the rest might survive.

It was here that Capt. Lampton, of Co. K, added his mite to the precious price paid for the maintenance of the Union. No soldier shed better blood than that man did. He had not the silly pomposity too often found in officers, but he had something better-a true heart in his bosom, a heart that went out after the interest of men, and a soul that did not flinch in time of battle.

On the 11th we moved a short distance to the left under heavy fire, and took a new position. The roar of muskets and thunder of artillery shook the earth with their fearful detonations.

Since the morning of the 5th our regiment had held a position in the front line-of-battle of its brigade, a fact for which I cannot account; unless it was believed by the War Department that the 126th Ohio could put the rebellion down if backed by enough men, or there may have been some pecularity about the regiment that the General desired to have it killed first that the rest might survive.

FRANCIS CORDREY, Co. E, 126TH Ohio, Ft. Wayne, Ind.

It was here that Capt. Lampton, of Co. K, added his mite to the precious price paid for the maintenance of the Union. No soldier shed better blood than that man did. He had not the silly pomposity too often found in officers, but he had something better-a true heart in his bosom, a heart that went out after the interest of men, and a soul that did not flinch in time of battle.

On the 11th we moved a short distance to the left under heavy fire, and took a new position. The roar of muskets and thunder of artillery shook the earth with their fearful detonations.

Since the morning of the 5th our regiment had held a position in the front line-of-battle of its brigade, a fact for which I cannot account; unless it was believed by the War Department that the 126th Ohio could put the rebellion down if backed by enough men, or there may have been some pecularity about the regiment that the General desired to have it killed first that the rest might survive.

It was here that Capt. Lampton, of Co. K, added his mite to the precious price paid for the maintenance of the Union. No soldier shed better blood than that man did. He had not the silly pomposity too often found in officers, but he had something better-a true heart in his bosom, a heart that went out after the interest of men, and a soul that did not flinch in time of battle.

On the 11th we moved a short distance to the left under heavy fire, and took a new position. The roar of muskets and thunder of artillery shook the earth with their fearful detonations.

Since the morning of the 5th our regiment had held a position in the front line-of-battle of its brigade, a fact for which I cannot account; unless it was believed by the War Department that the 126th Ohio could put the rebellion down if backed by enough men, or there may have been some pecularity about the regiment that the General desired to have it killed first that the rest might survive.